Selected Writing

Photo by Jordan Barse

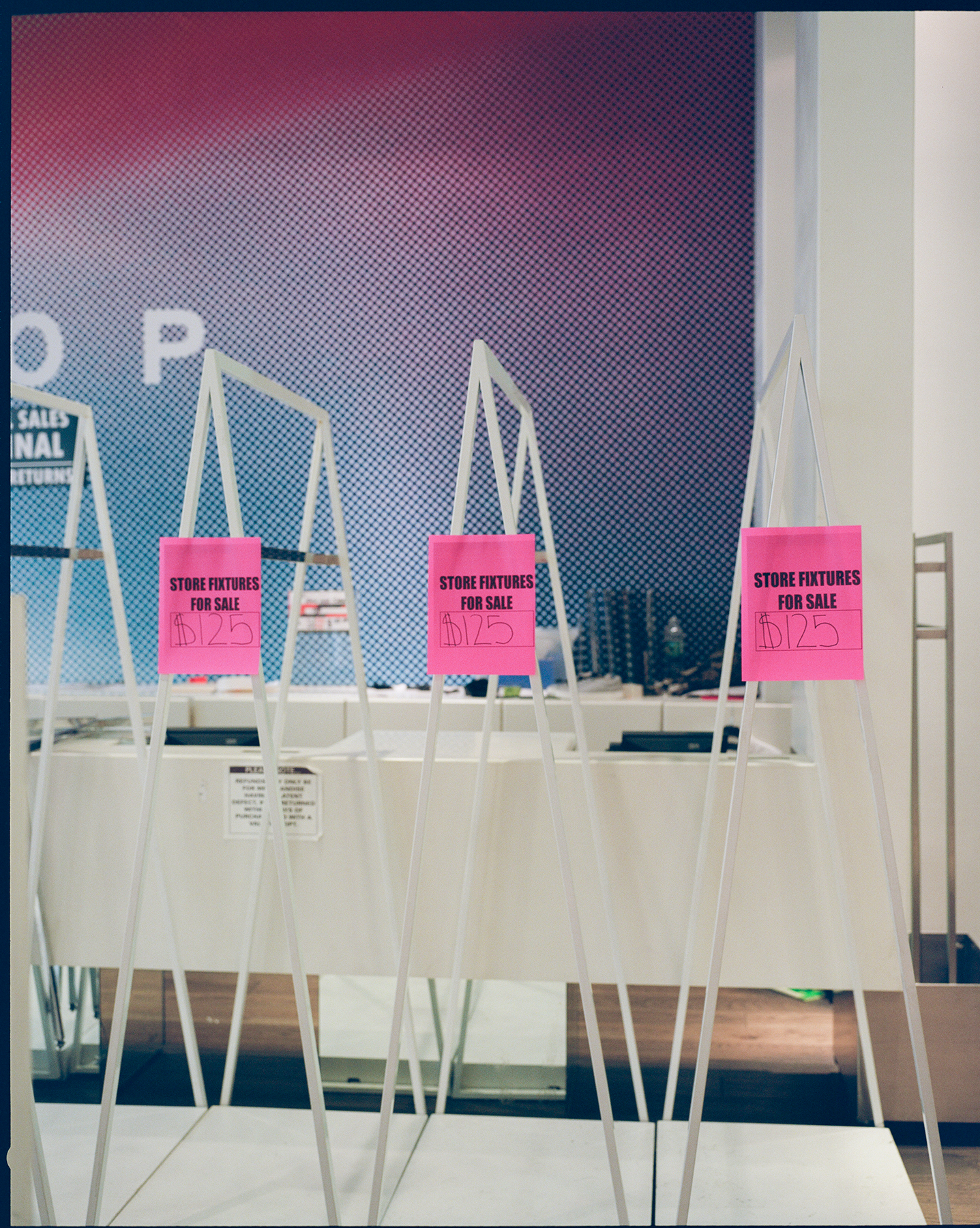

The reality of the thing is not so shocking as the urgency of its execution. Last week, across every American Topshop/Topman store, a smattering of red and black signs declaring EVERYTHING MUST GO! and 50-80% OFF! NOTHING HELD BACK! hung in clear view. The typeface was universally familiar and read distinctly unlike branded copy designed to lure you in for a fashionable, mid-season sale. This was something darker—a corporate blowout, a hand-off to a third party undertaker. This was bankruptcy.

Ten years ago, Topshop’s billionaire owner Sir Philip Green linked arms with supermodel Kate Moss atop a box emblazoned with a British crown as a veil lifted before the grand opening of the high street (read: British fast fashion) sensation’s US debut in the central artery of New York’s shopaholic heart: SoHo. It was April 2, 2009, and behind them, sunflowers hung optimistically from the ceiling, evoking an alchemical denial of the ongoing recession surging New York’s unemployment rate to a five-year high. The ambitious 25,000 sq. foot SoHo store boasted three levels of womenswear (including a hypeworthy capsule collection designed by Ms. Moss), a basement floor for men’s, and a zone for personal shopper services. Green wasn’t worried about his $24 million stateside investment, though, telling reporters: “People are still wearing clothes. They want to be inspired. They still want to shop. Get real.”

Photo by Jordan Barse

Topshop ruled the aughts, easily, building a phenomenal mass market empire that dictated trends as much as it mimicked them. With accessible prices and Kate Moss stamp of approval, its flagship in Oxford Circus was a London destination for shoppers who read Teen Vogue and NYLON religiously. The design team was composed of 14 young women led by Nick Passmore and Jane Shepherdson, and the competition for cheap and chic was virtually unmatched. Global chains Zara and H&M had their moments, but Topshop had its finger firmly on the pulse of the likes of Sienna Miller and the Olsen twins.

In a review of the Topshop Unique Spring 2007 runway collection, the only of its high street kind, Sarah Mower described the look as “somewhere between Chloé and Marc by Marc Jacobs, with a lot of the less 'designed' pieces looking on target enough to please the brand's millions of young followers.” It was no wonder, then, that Anglophilic shoppers lined up around the block for the chain’s New York debut.

Last week in SoHo, clearance placards had taken the place of sunflowers and a countdown ran to the final hour: Saturday at 8PM. On the ground floor, stacked cardboard boxes marked “FREE bottom hangers” greeted shoppers at the tiled entrance. To the right, hasty photo printouts of garment racks, back office furniture and appliances were taped to an easel under the heading “FIXTURES for SALE!” Upstairs, this proved true, as priced rows of empty metal racks and shelving units faced down an opposing team of naked mannequins huddled together with poise. Behind, the walls once covered with garments were stripped bare, revealing what resembled rough concrete to be a glossy trompe l’oeil wallpaper.

Agoraphobia loomed over the draining ground floor as massive glaciers of pre-distressed skinny jeans emitted dull whines of ambivalence. They know they’re burdensome, and they seemed to regret being made in the first place. The rest of the remaining offerings by week’s end weren’t too full of themselves either: oversize Christmas-themed sweaters in chunky, poly-viscose blends were marked down to $35 from $110. A notably chic pale yellow gown with scattered rhinestones and a ‘30s-style bias cut bore striking verisimilitude to silk, but its 100% viscose looked bedraggled with tugs among the thrashing racks, drained of ambition. Newsboy caps in every pattern the eye can see were lumped in a bin on the floor beside Halloween accessories and colorful scarves as big as blankets, an affront to the summer city heat. Bikini bottoms clung to plastic hangers like withering plants. All the bags were brown and depressingly practical. Downstairs at Topman, the dregs were somewhat more dignified; t-shirts galore, some funky suits. Nothing to write home about.

Photo by Jordan Barse

What happened to Topshop? Competition, first and foremost. Online stores with similarly fashionable offerings unburdened by the ball and chain of brick-and-mortar such as ASOS rose to international prominence as Topshop’s ace design team disbanded, seeking greater premiums on their prescience than the alleged abuse invoked by Philip Green’s bullying tenor. In 2013, ASOS’s gross profits more than doubled those of Topshop’s parent company Arcadia Group, and by 2017 Topshop reported an annual loss of about $14 million. Public statements from Green acknowledge Topshop’s inability to keep up with the pace and innovation of online competitors, but it goes deeper.

Just as the retail landscape evolved, so did the capitalist social. Instagram has spawned a commercial superhighway through which the feedback loop of ditsy floral dresses has so reduced garments of meaning that brands without distinctive identity–be that through represented ambassadorship or actually unique viewpoints (see: Brandy Melville and skinny 16-year-olds who make their 29-year-old English teachers nervous) or the lowest prices–seem doomed for failure. In fact, Zara’s industry ascendence could likely be attributed to its well-reported designer copycat squabbles, earning its rep as an irrefutable source of runway looks for less. Retail experts have pointed at Topshop’s internal scandals and unfocused efforts to establish stateside brand following as its Achilles heel, but browsing through Instagram, it seems plainly obvious that there is virtually no distinction between clothes sold by Topshop, Forever 21, Boohoo, Pretty Little Thing, Miss Guided, and H&M… except that all the others have lower prices, cleaner web interfaces, faster turnovers. Take this Topshop pleated snake print midi skirt, marked $75. ASOS has one for $24. Debatable scam SheIn has one for $17.

On Instagram, influencers gratefully tagging their gifted outfits to brands prioritizing social investment bring in millions as walking, Boomerang-ing #ad revenue, nearly all of which feel disturbingly repetitive. Lip fillers and off-the-shoulder ruffled chambray dresses before palm trees or crosswalks are ready currency for likes and perpetual @pullandbear freebies, an ouroboros of profit-driven pop aestheticizing. The indirect translation model of tabloids and teen mags to Topshop racks has been outmoded by Instagram’s greasing of the FashionNova wheel, spewing out ersatz renderings of a Kardashian’s birthday look in a fortnight, with free shipping.

Millennial shoppers are largely despondent about the loss. 26-year-old artist Isabel Legate recalled visiting New York to look at colleges in 2009, back when Topshop still “felt exotic.” “I remember getting off the double-decker bus with my mom specifically to go to Topshop and try on the Kate Moss collection,” she shared. “There was a moment when the brand felt very cutting edge. They brought in fresh CSM collaborators, downtown It Girl DJs… all of it.” After visiting the store this week, however, Legate concluded, “the magic was lost and it was really palpable. But what was the magic anyways? Fashion is ephemeral and I think I’ve lost the taste for this flavor along with everyone else.”

Consider this equation I developed a year ago:

‘90s nostalgia + Microsoft Paint color palette^banality + new 3D garment construction technology + snowboarders

÷ uptight fashion executive on business retreat in Chamonix Mont-Blanc

= unearthing the coffin of the Synthetic Fuzzy Sweater?!?

It first appeared on Balenciaga’s Autumn/Winter 2018 runway (The One With All The Coats) in acid green: its shaggy, sheeny, polyester fluffiness clinging neatly to its wearer’s shoulders; tucked into a belted, pleated, below-the-knee-skirt over black stockings and pumps (on some secretary shit)—and topped with a shiny blue carabiner necklace. The overall look was dull, but this was no ordinary sweater. “REMEMBER ME?” it screamed. I’m a millennial. Of course I did. But could this synthetic relic of the “Cool 4 School” section of a 2001 mail-order RAVE catalogue really rebaptize itself… into high fashion?

A model walks the runway at the Balenciaga Autumn Winter 2018 fashion show during Paris Fashion Week on March 4, 2018 in Paris. (Photo by Catwalking/Getty Images)

A season passed and I nearly forgot about my nostalgic itch—but then. There it was in the Marine Serre Spring/Summer 2019 show—an evolved Pokémon of frazzled acrylic in sun-bleached chromakey green, with an extra long scarf extension. Again it was paired with a below-the-knee skirt, and anodized dystopian accessories. A conspiracy was afoot! Why were two of the most prescient designers in Paris reviving artificial furry knitwear from the “90s Theme Party” section of 2011 Topshop? And why does the neon synthetic fuzzy sweater so readily associate with Y2K?

A model walks the runway during the Marine Serre fashion show as part of the Paris Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2019 on September 25, 2018 in Paris. (Photo by Victor VIRGILE/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Everyone knows the legend of the Sweater Girl: how, in the ‘40s and ‘50s, Western civilization developed heart-shaped eyes that sprung out of their heads on coils for young women wearing bullet bras beneath novel, tight-fitting sweaters. Boobs and the dirty thoughts they inspired were trending under the guise of modest knitwear. Like the words “Victoria’s Secret Angel,” “Sweater Girl” evoked a veil of purity in spirit over a willfully seductive exploitation of femininity. And her seraphic expression found its higher form in the halo of fuzzy natural fibers–mohair and angora–that, together with luxuriously prohibitive cost and rarity, framed the female form like a divine, well kept Madonna. Consider the canonical untouchability of Jane in Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas, sitting before the peep show glass in her backless, fuchsia angora shell. Yet, as the fashion industry is wont to do, it sought paths around inaccessibility. Polyester and acrylic fiber blends were developed and perfected throughout the 20th century to accommodate the proliferation of the fuzzy sweater, and in the process, redefine it.

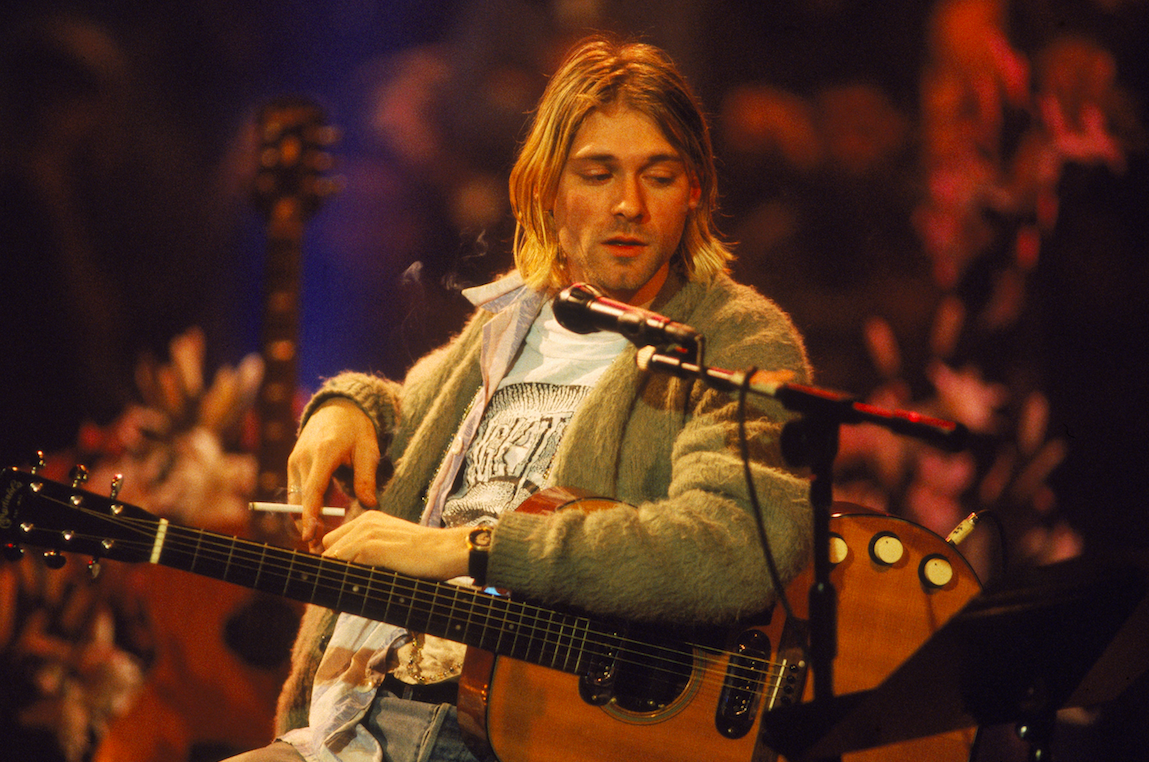

Only a year after Nirvana brought grunge into the cultural forefront, Marc Jacobs dropped the bomb that was his infamous Spring/Summer ’93 “Grunge” show at Perry Ellis. The gist of those repeatedly dredged-up, pearl-clutching Cathy Horyn reviews is that the collection shocked people because it demonstrated an inverse exchange between high and low fashion. If grunge was about “un-fashion”, or abject thrifting, Jacobs recycled that old piss and fermented it into expensive Chardonnay. Real grunge-heads hated it, too. But no sooner had Jacobs been fired as creative director than “Grunge and Glory” spreads hit the pages of Vogue, prompting generic labels like XOXO to manufacture the equivalent of Diana Wine to feed the widespread appetite for grunge. Teen shoppers emblematized grunge as an iteration of The Latest Fashions, not a Salvation Army binge. The $40 fuzzy sweaters teens bought that came from photos of Cobain in grandma’s mohair on the mood board in the Forever 21 design HQ? They’re polyester.

American singer and guitarist Kurt Cobain (1967 - 1994), performs with his group Nirvana at a taping of the television program 'MTV Unplugged,' New York, New York, Novemeber 18, 1993. (Photo by Frank Micelotta/Getty Images)

After Kurt Cobain committed suicide, fashion reexamined its relationship with glamorizing apathy. Incidentally, the Sweater Girl was reclaimed, turning the inside-out, back rightside-in. A 1994 Fall Fashion review in the Times proclaimed: “If the slip dress was a coy summer flirtation, winter has turned a bit more explicit. Welcome back the 1950's Sweater Girl, her ample fuzzy bosom clad in deep mohair.” Liv Tyler was a small town girl with big hearted ambition in a blue cropped pullover in Empire Records and Alicia Silverstone promoted her flirty teen dream flick, Clueless, in an even more cropped baby pink angora.

"Empire Records" still via IMDb.

By 1997, pop culture was cleaning up its act or moving to LA to drop acid, as in the supersaturated rave parties and high school hallways of filmmaker Gregg Araki, creator of the “Teenage Apocalypse Trilogy”– Totally Fucked Up (1993), The Doom Generation (1995), and Nowhere (1997)–featuring abundant candy-colored synthetic style. Araki’s queer indie capsules of lost and disaffected youths on the brink of ungodly disasters hyperbolized the manic pop energy of a generation that felt dragged through the ‘90s, and cynical ad absurdum about the end of the 20th century.

Real-life global panic set in as Y2K’s potential domino collapse approached, and fashion wrapped itself around neodrama like a snake on a scepter. Of course, by the end of the 20th century, synthetic textiles were not just ubiquitous, but essential–furry imitations and out-of-this-world inventions defined the “End of an Era” look of euphoric nightlife escapism. Led by pulsing techno beats and Ecstasy-induced “childlike amazement at the here-and-now,” ravers found sensual satisfaction in the supersoft “monster furs” and neon accessories that glowed fluorescent day or night, and were titillating to touch. From UK forests to LA warehouses, the synthetic fuzzy sweater fit well in a culture primarily focused on optimizing your vibe. World’s ending; might as well party! Or, from the optimist’s perspective: the Millennium’s coming; better dress like it.

The Millennium brought Verner Panton fantasy interiors and spikey hair with frosted tips, metallic jeans, empowered cyberpunks and Oops!... I Did it Againpop futurism. Gone were the days of mohair mimicry; Synthetica was IT. For a minute, it felt like we might leave the natural world for good. Maybe we’d never look back at the 20th century ever again… Or maybe not.

Back in the ever-advancing present, I solved the equation with the help of a magic mountain. Balenciaga’s Autumn Winter 2018 rendition of the neon fuzzy sweater looked a lot like that of the anxious, anticipatory pre-Y2K years, but the collection’s overall tone was one of a semi-professional, mid-90s purgatory—these bright, young things have JOBS and they’re going to work for the bright, liberal, corporatized future. Any question of their outlook on life can be answered by the giant, fake mountain set in the middle of the show’s runway, brimming with encouraging graffiti tags beside neon BALENCIAGAs and AW18s: pride flags, block-lettered “LOVE”, “power of dreams”, and “you are the world”. Demna’s sweaters were bursts of hope; denials of glib reality!

Balenciaga Ready to Wear Fashion show at Paris Fashion Week Fall/Winter 2018/2019 on March 4, 2018 in Paris, France. (Photo by Victor VIRGILE/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

With one query essentially pinned down, I set out to solve the other—that Marine Serre overlap—and got more complicating evidence than I bargained for. Initially the references seemed rather explicit: “FUTUREWEAR” logos emblazon half the garments and alien-tech bubble bags, reminiscent of Stepsister from Planet Weird (2000); they basically screamed celluloid futurism. While it’s possible that both Balenciaga and Serre built their narratives on preempting the end of the ’90s, I suspected something deeper was afoot. Across generations, the fuzzy sweater has become a bellwether for radical newness and a catalyst for gender redefinition. And what about the color?!

Chromakey green was easily the It color of 2018, and the huey expression of a future realized through media. Marine’s looks are intertwined with tech-y media, from their performance-wear headphone holes to their bombardment of logos. Messaging, messaging, messaging. Nonstop listening to podcasts. Serre designs for our synthetic future in which we cozy up to polyamide fibers and wrap our offspring in matching print-meshed baby bjorns. Perhaps in this high fashion future we acknowledge the 2018 PETA investigation into rampant abuse of angora goats in the mohair industry that has already led to more than 300 fashion retailers banning the sale of mohair in their stores. Marine doesn’t claim to build her practice around political platforming, but her animal-free textiles and upcycled scarf and t-shirt designs come with the territory of her self-proclaimed “equilibrist” interests in collaging.

Real Crescent-heads will recall that Serre herself famously worked as a design assistant for Demna until some months after she won the prestigious LVMH Prize for Young Fashion Designers in late 2017, just a few months before Balenciaga showed that very collection, in March of 2018.

Former GARAGE editor Rachel Tashjian recalled seeing Marine in adifferent synthetic fuzzy sweater when she interviewed the designer this past summer. In Rachel’s recollection, the designer confessed she had purchased the sweater on the street in New York. Could Demna have plucked the idea from Marine’s own wardrobe--after which Marine herself then parlayed it into her own iteration a season later? Does knowing the truth behind a designer’s textural inspiration detract all substance from the lies we tell ourselves to give meaning to our consumer impulses to buy everything old once it’s renewed and expensive again?

Perhaps what these two sweaters have to tell us is that notions of luxury must shift. Once lauded for softness, rarity, and speciesist denial of the likely abuse of animals whose hair composes them, natural fiber knitwear may be receding from the luxury spotlight. Perhaps in this next phase of futurism, we relish in the fair trade flocculence—I tried on the Balenciaga piece, and let me tell you: it is SOFT—of our chemically-perfected, nouveau fuzzwear. In a late capitalist world that’s fast depleting its natural resources and overburdened with dark chaos, Serre and Balenciaga are making optimistic alternatives the latest luxury. Let the chromakey fuzzy sweater be the green light of our orgastic future that year by year recedes before us, bundling us through the whiplash of hyperreal macabre news cycles, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

In part, I attended the event because Westreich Wagner is a legendary tastemaker and patron of the arts (and I wanted to catch a glimpse of her intimidatingly chic stature in hosting mode. What would she wear?!). Then there was the program, which included “an operative presentation” entitled MARX PUNK, and Strange Teaching, “a standing sculpture to be not noticed for about 15 min,” per the event program.

Manhattan Marxism, edited by Rachel Corbett, contains writings by Ganahl and others from the past decade, contextualizing its publication 10 years after the global financial crisis and 200 years after Marx’s birth. Corbett insisted it is not, in fact, “a Marxist book,” but a study of matters like “the fast fashion phenomenon…filtered though the lens of Marxism.”

When I arrived, MARX PUNK was already underway, with two opera performers trilling lines like: “Tinder Marx—fuck yourself / Grindr Marx—fly SpaceX” and “Q: Marx language / A: Marx speaks Chinese / Q: Marx Africa for sale / A: Alibaba Marx / Q: Snake head dress for $5,100 / A: Gucci Marx”—with apparently no prescribed melodies.

Book mood.

Three young people stood silent and barefoot at edges of the lofty room, donning white, neo-Buddhist straightjacket-type outfits with constricting accessories that required them to either press a stack of novels against a wall with the side of their head, bend one leg against the other calf, or fold an arm to encircle the head. These were the sculptures I was meant to not notice, obviously.

Pinned to the stage’s front wall was a printed silk Hermès scarf—not unlike one I’ve been lusting after on the RealReal—with the words “HERMÈS MARX” screen printed over its center, surrounded by yellow vests, the sartorial symbol of this year’s French populist protest movement for economic justice.

Standing beside the performers was a man in a distinctly so-deep-in-the-art-world-no-one-can-check-me outfit: thick, plastic-rimmed orange sunglasses, silk Hermès neck scarf, T-shirt, and a navy double-breasted suit patterned with a gray cross-hatching pattern of text that read, alternately, “Please, teach me Chinese” and “Please, teach me Italian” in various languages. He was moving around with his Android phone up, documenting the opera and the audience erratically, performing an almost Chaplinesque caricature of Established Artist. He was Rainer Ganahl, obviously.

Slabs of cardboard on the floor lay on the floor displaying stacks of Ganahl’s books and editions beside two Gucci accessories—a backpack and fanny pack, beneath hand-scrawled signs that read “UBU TRUMP, $6.66“ and “COMME DES MARXISM 5$⁵.” As the performance stretched on for nearly 30 minutes and Ganahl continued with his cinematography, I couldn’t help but giggle, despite the devastating fact that Westreich Wagner had already departed and we were out of wine because half of it had been accidentally frozen.

After it ended, Ganahl talked about the performance while the audience in the back chatted amongst themselves, not at all listening, which didn't seem to bother him. He explained that he had designed this suit as part of a project commissioned by the Italian city of Prato, once the capital of the luxury textile industry and manufacturing source for brands like Gucci and Prada, now home to the largest concentration of Chinese immigrants in Europe and a hub for fast fashion manufacturing and illegal labor practices. The Italian government had commissioned Ganahl and Yoko Ono to create public art projects that might help bridge the hostile sociocultural divides between Chinese immigrants and Italian natives in what has become an extremely contentious and crime-driven city. Ganahl designed the multilingual textiles in line with his preoccupation with learning foreign languages and his belief that knowledge begets understanding and unity. Despite the artist’s best intentions, however, the suit’s very presence on his body demonstrated a litigious victory against the textile manufacturers who had soured on their deal and withheld his custom suiting for some time.

Then came my favorite part. Mr. Ganahl climbed up a ladder to project a video from his precariously balanced laptop that he filmed outside of the Gucci store beneath Trump Tower. He expressed something like outrage that the LCD screen behind the mannequins in the Gucci flagship’s window display featured chopped up segments of Lindsay Anderson's 1968 film If..., an über-violent social satire about anarchy at a British boarding school. He decried the juxtaposition between the film’s central imagery of kids with guns (which Gucci cut out! Shady!); Trump Tower; the gaudy feedback loop of Gucci’s luxuriously ebullient appropriation habits; the street vendors selling fakes on the curb in front; and Gucci security trying to prevent him from filming the window. Why couldn’t I stop laughing??

Ganahl’s whole presentation seemed to be about the fallacy of aestheticizing Marxism in fashion, but it landed like an endlessly wandering doggerel of unfinished thoughts tracing blind contours around global politics and fashion. The dots between Prato, Gucci, Chinese manufacturing, Trump, Anarchy, Meaning, Meaninglessness and Mistrust were laid out, but perhaps the most compelling aspect of this Boomer-with-millennial-preoccupations’ act was his inability to express what it is about Gucci (among other major brands) that feels overwhelmingly immoral at the same time as enticing. In what felt like a dandy pratfall of a Marxist critique the artist essentially provided comic relief, intentional or not, of our powerlessness in the face of the fashion industry’s political messaging.

Fay groaned dramatically, sliding from the edge of her bed to the floor and into position: shoulder blades flush with the bed frame, feet flat on the Gabbeh rug, wrists on knees, eyes fixed ahead on her screen as she tapped through the banality of everyone’s Insta stories. The air conditioner blasted from the window in front of her as the sweat that had been fusing her silken, oyster-hued ’90s Marc Jacobs slip dress—vintage, not grunge revival—to her slender frame began to evaporate, unshackling her from New York City’s oppressive late summer heat.

Fay had been out for the last 14 hours, grinding through work at her glorified retail job; touching up lipstick in the dirty reflection of the subway’s glass windows as the car passed through darkened tunnels; perching on vinyl-cushioned stools at Big Bar and then Boom Boom Room; crouching intermittently to retie the white kid leather lace-up straps on her Martiniano Pavone sandals as gravity brought them to a layered clump at her ankles. Then pressing her back against the tiled walls of some unlocked prewar office building on Horatio Street as Ryder kissed her salty neck and pushed the bulk of his weight against her through his black Acne Studios Max slim fit jeans, his fingers finding their way into her Kiki de Montparnasse striped silk satin thong and…She needed sleep, but she wasn’t about to contaminate her sacred white Pratesi linen cloud of a bed with all that sweat, precum, and grime. In fact, okay, fine, she’d shower now. Then bed.

It was 4 a.m. by the time she slid under the beautiful eBay-derived covers, but she didn’t have to be at work until noon. Fay lay awake feeling fresh, desirable—and bored. Why did it always feel like she was right next to the action but never involved? For starters, she was shy. Fay had studied French New Philosophy at Bard, and when that didn’t immediately translate into a lucrative career, she got a job at Pistopinto selling designer clothing and accoutrements to the kinds of downtown arts and culture people Bard used to bring in for guest lectures. The event that Ryder had brought her to, at the Boom Boom Room, was cool and all—an after-party for a film screening at the Whitney Museum with a private Jorja Smith performance—but she didn’t know anyone there except him. As the Whitney’s senior development coordinator, Ryder was looped in on all the cool goings-on, but he wasn’t exactly friends with the Eckhaus Latta-wearing camarillas that ran the scene, nor did he look like it. Fay nearly gagged at the sight of his slicked-back hair and Common Projects sneakers when they met up outside the Standard. What was he, a design bro now? She liked his company, but she’d made it clear from the first that this was to be a casual affair based on convenience. The vibes just weren’t there. Finally, thoughts of Ryder bored her to sleep.

Fay made it halfway through the workday at Pistopinto without feeling a hangover lag. She had on her standard uniform: a well-worn vintage T-shirt, brown pleated-front trousers with washed denim backs from the Berlin-based line Bless’s collaboration with Levi’s, and her metallic Margiela Tabi d’Orsay heels. Her feet never got tired; good genes, or whatever. She’d been a sales assistant there for a year now and, for her, that “2:30 feeling” usually hit closer to 5. Maritza, her favorite coworker, was on her knees across the grand, artfully decaying floor trying to scrape a pair of multi-cuffed Y/Project jeans off a genderless chrome mannequin. The mannequin’s legs stood straight in defiance as Maritza bowed her head into its smooth, politically correct crotch in resignation.

Fay crossed the century-old marble-tiled floor. Pistopinto was situated in a former bank building that had been left to crumble before it was bought by a photographer in the ‘60s, became a grunge club in the late ‘80s, and only last year realized its God-intended form as an enchantingly apathetic destination for chunky Dries Van Noten sandals, $800 graphic hoodies, and Issey Miyake bud vases.

“Do anything fun last night?” Fay asked.

Maritza turned over her shoulders, still clutching the mannequin’s ass. “Not really,” she yawned, adjusting her pearlescent red Seoul Import hair clip. “Just went to some skater party at this new reno loft in Dimes Square.” She thought for a second, then smirked. “I did meet these guys who said they’d come by the store today––”

The clouds shifted in the sky, beaming fresh light through the windows. “Names,” Fay demanded. “Cute?”

“Ugh, I don’t even know. One of them was, but I didn’t talk to him. He had like a Secret Service of boring Instagram girls on him every time I turned around. But he was soo cute. The other guys were like, super sweet but they had on way too much Bape. Is Bape a thing again? Or still?”

The front door chirped as a pack of boys no older than 22 ambled through the gilded double doors. “Oh, wow, that’s them,” Maritza whispered as her hands shimmied up and down the mannequin’s toned thighs. Fay nodded and began finger-spacing hangers along the curved armature of a Calvin Klein 205W39NYC display rack as the dripped-out crew began pairing off across the sales floor, half of them just barely looking up from their phones to make sure they didn’t trip on the split levels. Three of them wore boxy, indiscernible streetwear and Reebok or Adidas sneakers that might as well have been invisibility cloaks to Fay, decorated stiff with esoteric screen prints and cargo pockets to hide the softness of their unconcerned bodies.

One looked fresh off the runway archives of Raf Simons’s legendary 1998 “Black Palms” show. His loose knit top slunk over his baggy gray Our Legacy trousers and racing red and white Salomon S/Labs in a way that looked breezy, European, and dumb.

And then there was Camrin Abbas, who she recognized instantly. He staggered behind the others, physically transforming the energy of the store with his nonchalant hotness as he squinted into the glare of coruscated sunshine. She’d seen pics of him at every important fashion show, rap album listening party, and Kardashian birthday; he lingered cooly in a paparazzi shot of Jonah Hill and friends on Crosby Street. She’d also glimpsed him at a select set of blue chip gallery openings. He looked like a walking ad for the concept of youth culture—and, in fact, hadn’t she just seen his face on those new ads all over the city for Fiji Water or something? His shoes were custom NikeLab x Off-White; his pants, she knew, were Balenciaga. His clean white T-shirt looked like it had probably cost $350, and over it he wore a (gifted, obviously) pre-release Louis Vuitton white vernis chest-holster bag, fresh out the showroom from Virgil’s inaugural menswear collection.

Fay darted her watchful gaze back to the racks before her as Maritza greeted the crew with zeal. Fay internally ran through a litany of brands that might have made Camrin’s T-shirt: Stone Island? Off-White? (But would he really do that much Virgil in one fit? Probably.) Rick Owens, Berluti, Comme des Garçons, Prada, Saint Laurent, Jil Sander, MM6, Lemaire, Acne Studios, Tom Ford, Visvim…

A smooth, liquid voice came from behind her. “Hey, uh, do you work here?”

Read part two here.

Copyright Jordan Barse